| Vol. 1, Issue 4 | |

|

Midtown Mojo By Marc Lefkowitz In the midst of an economic recession—with RTA and Cleveland facing millions of dollars in budgetary shortfalls—now is a perfect time to examine The Downtown Planand the sometimes half-hearted attempts to fulfill it. The Euclid Corridor Transportation Project is a collaboration between the development corp. MidTown Cleveland, Cleveland and RTA. Executing the plan so far has included knocking down some buildings that precious few care about, and planning for the $220 million dedicated bus lane, a redeveloped streetscape and spruced up transit stops. Kudos for efforts to secure a bike lane, but is there room in the buttoned up development agenda of Midtown for something more than the bland, single-use office boxes plopped down from a suburban office park? Perhaps the future Euclid Avenue will be pictured through the lens of what this corridor once was—a thriving, walkable, transit-oriented neighborhood.

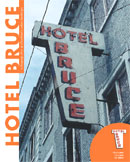

The tale begins on a blustery day in October (2001) in Cleveland. Against the backdrop of weedy abandoned lots and the remains of Euclid Avenue’s pre-war walkups, an eight-story crane sends a wrecking ball like a Thome laser shot crashing into the 80 year-old walls of the Hotel Bruce. Spitting distance from the smoldering pile of bricks and wood, a demolition crewman squints under his blue-hooded workcoat. “I dunno what they gon’ build,” he says, barely audible, as a cold rain begins to fall. “I just hope they doin’ something for the neighborhood.” Discolored, windows blown out, but defying time on this neglected corner of Euclid Avenue and E. 63rd Street since it was boarded up in the late 1970s, the Bruce is meeting the fate of so many buildings from that era. Why now? Because the land under the hotel on this

long forgotten stretch of Euclid Avenue is suddenly at the epicenter

of a “new” city plan. Urban planners and business honchos

envision a biotech office park cast out of the rubble. For others,

like this stooped gentleman on the demo crew, the plan seems filled

with as many holes as the pockmarked hotel. In his simple statement

is a point planners and politicians might want to heed: We

have ideas for how this neighborhood works. Long before the Single Room Occupancy “red light” days of the 1960s and ‘70s, the Hotel Bruce and many others that lined Cleveland’s “grand avenue” were jumping with activity. Blue-collar immigrant workers, visiting vaudeville acts and jazz musicians gigging in nearby joints all made their way to the hotels and bars along Euclid Avenue for the late night scene. A melange of jazz and vaudeville, waltz and the two-step, swing and bebop ran in the veins and arteries of this area. It wasn’t until later that the so-called red light era would signal the end. Red light was a reality in almost every large city such as Cleveland and it helped foster an anti-city bias that came of age in America after the 1950s. But it was not synonymous with poverty. On the contrary, Cleveland had its fair share of the racy and obscene as well as the sublime and fertile period of the Jazz and post-Jazz age.

In the 1930s and 40s, Euclid and Hough avenues werre considered the red light district for white folks, while Central was where you could find the “fast action” if you were young, black and looking for a place to relax, recalls jazz saxophonist Andy Anderson. Jazz also offered one of the few places blacks and whites could come together in the “black and tan” bars that drew mixed crowds. Another shared interest was the prospect of gambling, drinking and good times. “The red light district was where they hustled,” Anderson says. “If a person wants to make money, they put the red (porch) light on, and that means there’s going to be gambling and entertainment and prostitutes, sure. Every major city developed the same way. Look at Harlem, Chicago or any big city— you’re going to have entertainment and that’s where you’re going to find the action.” At the same time, the dizzying popularity of jazz and vaudeville acts were drawing big crowds into the city’s “legit” dance halls, and that fed a boom for restaurants, clubs and more theaters. Central was one hot spot of activity. Around E. 55th and Woodland, vaudeville ran at the Grand Central and The Globe theaters. Karamu, then a small storefront, staged musicals; and clubs such as Cedar Gardens (at E. 95th and Cedar) booked the big jazz acts of the day. Euclid was another Eastside spot. Mostly white-owned dance halls located from E. 105th west to E. 55th were packed with crowds going to the theater or big band. The popular venues were Zimmerman’s, the Crystal Ballroom, Dreamland and Oster’s Ballroom. After the shows let out, musicians and scenesters would make their way down Euclid or Central to neighborhood whisky joints (the Hotel Bruce was just one of many), Anderson says. The popular spots had a piano, maybe a late night menu and some gambling and private parties going on upstairs. It wasn’t all bad and bawdy. Anderson, who gigged with both Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday, has fond memories of playing for children from a school for the blind located on E. 55th and Quincy. “We played waltz’s, one-step, two-step,” he says. “And they could feel the rhythms of the drums through the dance floor.”

Around the Hotel Bruce (built in 1922), Hough was filling up with retail shops and manufacturing jobs. Large employers such as Pennsylvania Station at E. 55th and Euclid, the (huge) turret lay manufacturer Warner & Swasey at E. 55th and Carnegie, and a cluster of textile mills were within walking distance. Streets were densely developed with Cleveland doubles—the kind of homes with expansive porches and people visiting on them (housing stock you might see in Glenville today, but long since demolished here). People chatted while waiting in line at the bakery or the butcher, neither of which were self service. “We had different classes of people and different thinking,” recalls John K. White, whose family lived at E. 79th Street and Hough Avenue until the late 1940s. “Hough was a mix. At East 66th you had the Irish. Glenville was primarily Jewish. North of Wade Park was Central European. And Mayfield was Italian. But around East 55th from Payne to Superior, it was mixed [race] by block.” Nearly everyone walked or hopped on a streetcar for a three-cent fare to jobs in the industrial Flats or maybe to see a show at Public Hall. Three bowling alleys were within walking distance and two movie theaters were at E. 55th, recalls White. One of them screened foreign, mostly Russian films. “A lot of Communists lived near there,” he adds, “on account of the Depression.” Still sporting a goatee, White, 81, a former copywriter and currently an advisor with SCORE, says that the European immigrants and the black families of Hough in the 1930s and 40s got along fine. “But after the war, a different type of (white) people moved up here from (Appalachia) and then colored people from Central moved in. And they didn’t get along.” History tells a slightly different story. While it’s true that hundreds of African-American families living in Central were dispossessed of their homes in the 1950s due to the federal government’s Urban Renewal program which cleared “blighted” areas, the turnover of Hough was really exacerbated by racial and housing discrimination. Before the Federal Housing Act of 1968, the pernicious practices of racial steering and blockbusting—where real estate brokers scared white home buyers into selling quickly by convincing them their neighborhood was being taken over by “minorities”—effectively turned over the race of many blocks in Hough. It was legal and highly effective in churning Hough, says CSU urban planning professor Norman Krumholz. Despite perceptions, this area of Euclid didn’t just fall off an economic precipice after white flight in the 1950s and 60s, according to former Hotel Bruce owner William Seawright, 96, in what may be his final interview (he passed away in April, 2003). The area and the hotel was still a popular gathering spot at the time for residents, ward councilmen, Cadillac-driving businessmen, or members of the Sixth City Golf Club returning from a round at Highland Golf Course. They all filed in for Angie’s soul food and stuck around for a shot and a beer at the Playbar. “The neighborhood deteriorated gradually,” explains Seawright, who ran Fairfax-based property management company Seawright Enterprises and was a reputed numbers runner. “During the time I was there, people did a lot of traveling on foot from Euclid over to Cedar Avenue.” That was before Pierre’s Ice Cream factory blocked the thoroughfare.

By the early 1950s, the hotel business dried up and Seawright stopped renting out rooms. A decade after musicians and hep cats crashed at the Bruce, the floors upstairs were now empty. Which meant Seawright had to put his grandiose expansion plans on hold. “I couldn’t go through with what I attempted which was to put in a rooftop garden,” he says. “I had in mind a restaurant on the roof. But, I didn’t have the money to fix it up like I wanted.” What happened along the way? History. And much of that red light period is not worth mentioning. Still, what will Cleveland’s Downtown Plan amount to if this slice of the city does not consider the full scope of its history, and once again anchor commercial development and the prospect of new jobs around a mixed-use, pedestrian friendly district? The crane punches into the brick walls, making way for the plans of a new century. One filled with dreams of biotech boxes where computer geeks and scientists will punch in and, at the end of the day, hurry off to life in the suburbs. The critics of Euclid Corridor recognize its weakness—transit before development. They worry that even transit-oriented development doesn’t guarantee buildings that are designed to the street, that have a ground floor presence and a human scale. But, creating the opportunity for a transit-oriented development with, for example, nodes of retail and commercial space (and perhaps apartments above) is not impossible to conceive here at E. 63rd Street or at the transit stop near Gallucci’s. It might also serve to silence the many critics of the Euclid Corridor project who, rightfully, some might say, complain that transit alone cannot spur development. Creativity is needed here too. Next, Part II of the Euclid Avenue story. In

Winter 2003, we'll show the results of an artist/urban planner envisioning

what type of building could go on the site of the old Hotel Bruce

considering the history and context of the street, including the

plans for a biotech park. And we take a look at the developments

underway today on Euclid Avenue and explore how it takes a few pioneers

and, sometimes, a lot of pressure to change an abandoned area. Do you remember the Hotel Bruce or Euclid Avenue from back in the day? Have a good story about either one or both? Email us. Or, click here to see other reader's memories of the Hotel Bruce.

|

|

What's Feature Well? What would the city look like if the new guard were in charge? Each issue focuses on an area in the city that could benefit from some creative energy with feature articles that offer a vision for a new Cleveland, Q&As with the movers-and-shakers who are making a difference, and visual evidence of how the landscape might look if creatives were calling the shots. |

Once Upon a Rustbelt | Party Center | Raw Materials | Subscribe | Urban Underpants