| Vol. 1, Issue 4 | |

|

What can Cleveland learn from Germany's reuse of industrial relics and urban land? Words: Birgit Wolter Cleveland is an odd town to a foreigner. The appearance of the core of Cleveland is that of a normal city: High density, sky scrapers, traffic and business. Like many large cities, there are a lot of vacant shops, beggars on the street and other signs that Cleveland has obviously had better times. In spite of this, the urban fabric is still working.

In its good urban patterns one sees that Cleveland has a lot of potential. One problem is that these patterns are not connected. Tower City and Playhouse Square are areas in downtown that work pretty well. University Circle and neighborhoods like Little Italy or Bratenahl are other examples of, more or less, healthy parts of the city. But what is happening in between these parts? Not that much, as you realize when you are walking through East Cleveland or Glenville. The structure is run down, buildings are vacant and a lot of shops are closed. How could this happen? Why did people leave these neighborhoods? “Shrinking City” is a term everybody talks about today. It seems to be a super-modern phenomenon. But, throughout the history of human settlement, cities grew up and died. Isn’t it just a normal development that people leave a city to live somewhere else, where they can find better living conditions? What is new with this current case is the dimension in which cities are dying. I don’t want to suppose that Cleveland will actually die, but to be honest, if you walk through some areas, it looks very much like that. There are two possible reactions to this situation. The first possibility is to do nothing and let the areas die. The second is to try to stop this trend. To do nothing seems to be the easiest and cheapest way to handle the problem. Let everything become run down, give the area back to nature and wait until a new ecosystem will be established. That sounds good; it’s a vision of healthy ecological spaces that surround what are now considered suburbs. These areas would become small villages and Cleveland would cease to exist.

But does it work? Who will pay for the infrastructure that allows every citizen the access to all needed services; including the poor or elderly people who can’t drive a car? Will every small village have its own hospital? Who will pay for that? The benefit of a city is that the whole infrastructure can be concentrated and serve many people. In the end, the solution to invest only in the small villages might not be the cheapest way. Maybe it would be cheaper to stop the city escape that is happening in Cleveland and to turn the trend around. Giving up so much existing urban fabric can never be a satisfying solution. Cleveland, like a Sleeping Beauty, has so much potential – gorgeous buildings and green spaces – that it would be a pity to lose it. Reaching for Cleveland’s potential Situated on a lakefront, Cleveland has a beautiful and very special location. The only regrettable thing is that the lake is not perceivable. Cleveland could have a fantastic lake promenade where families take a walk on Sunday, people in-line skate, bike and run. But the city turns its back to the lake. Further, Cleveland has beautiful building stock in the neighborhoods. For example, East Cleveland and Glenville with their large, wooden single-family dwellings, gardens, old churches and quaint avenues. Rockefeller Park, with its lovely monuments dedicated to the different nations that live in Cleveland, could connect the lakefront with University Circle and its cultural amenities just around the corner. All of those elements seem to be qualities that would make them successful neighborhoods, but everything is in terrible condition. This region around Rockefeller Park could be a site to redevelop a greater inner city area by using the potential of the existing environment. Why not try to develop a new vision for Cleveland´s future on this site with a building exhibition? Bring together architects and urban planners, landscape artists and teachers, inhabitants and politicians and let them create a model for Cleveland´s urban pattern of tomorrow. IBA Emscher Park – a model for urban revitalization

An example for the creation of a new vision for a former high industry region is the redevelopment of the Rhein-Ruhr region in West Germany. The region had a negative reputation as an air-polluted, ground-contaminated area as a result of the ecological devastation caused by coal mining and steel production during the last century. In the 1980s, the exploitation of resources came to an end, and a new vision was needed. It was decided to organize an "IBA" in this region. IBA is the abbreviation for the German term Internationale Bau-Ausstellung or International Building Exhibition. In 1901, the first German building exhibition took place in Darmstadt followed by a series of building exhibitions including the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart in 1927 and the IBA in West Berlin between 1979 and 1989. As an instrument to develop a regional planning strategy and to demonstrate it by initiating exemplary projects, an IBA is a ten-year program funded by the local and national governments, the European Union and public-private partnerships.

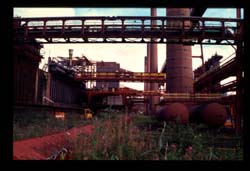

Starting in 1989, the IBA Emscher Park focused on an 802 km2 area surrounding the small river Emscher including 17 cities and a population of two million inhabitants. The vision was for an ecological and economic renewal of an old industrial region and the strengthening of the regional identity strongly impacted by the filth, danger and difficulty of working in the mines. For 10 years, approximately 120 projects were implemented with the goal of sustainable redevelopment of industrial sites, the preservation of industrial monuments, the creation of a huge, coherent green area for the whole region and several residential settlements. The Emscher Landscape Park was a redesign of former industrial sites with the objective to create a park that was characterised as an “urban wilderness”. Industrial monuments such as chimneys or unused railways were preserved as landmarks in the natural landscape and supplemented by pieces of art-like sculptures by Richard Serra or Ulrich Rückriem. Steel ovens were converted to performance spaces or climbing trails. The former smelting works are now used as high tech centres, founder centres – places that offer cheap work space for young entrepreneurs – or cultural institutions. The redevelopment was accompanied by an improvement of the ecological system in strengthening the natural water circulation and filtering the sewage. The result of this work is a return of plants and animals to their natural environment. However, this was only the beginning of a long-lasting process. An IBA is an instrument to create ideas and to push a new development in a region. Now, after the first steps are done, the process will continue its way (currently a new IBA, the IBA Fuerst Pueckler Park, tries to transfer this concept to a similar situation in East Germany). A Cleveland IBA? Looking at IBA, could we see a vision for Glenville that could then be translated to all of Cleveland? Some of Cleveland´s problems seem to be the location of industry, the pollution of the natural environment and the declining state of public schools. Let’s use the vacant land of Dike 14 and imagine that maybe this sort of paradise for birds is the anchor for a new start. Maybe Dike 14 will be an ecological zone, a place that nature restores. People can walk through this area over boardwalks, and enjoy the birds, the plants and the lake. Dike 14 could be the showpiece of a green Glenville, or “Greenville” if you like. A (proposed) new RTA line could bring people from Tower City to Glenville in only 15 minutes. Wide, green bridges over the Shoreway could connect park and dike. At the north corner of Glenville, like a node between the green space and the neighborhood, would lay the new green school (now Charles H. Lake Elementary, which is slated for rebuild). This school, built in a sustainable way, would not only be a green school from outside but would also have a green education program. The understanding for the complex processes of ecology and the experience of nature by field trips would be part of the program as well as learning about new sustainable technologies. The neighborhood that belongs to the school would be a mixture of reconstructed old and new building stock. The new buildings would be low- or zero-energy houses, some of them offering studios or workshops in addition to the residential use for owners who want to work at home. Some of the residents might work in the former industrial stock that would now be reused for cheap, big, natural-lit work lofts, office space or ateliers. Halls would become performance stages or galleries. The old industrial structure would look beautiful and rough, as a reminder of the history of Cleveland. Cleveland had a great past, but let´s face the future.

|

The old industrial structure would look beautiful and rough, as a reminder of the history of Cleveland

| What's Eco-ing? We bring you ideas, activities and people who see Cleveland in an eco-friendly light. Past issue |

![]() Also in this issue's Ecoing...

Also in this issue's Ecoing...

Our urban designer's plan to enhance connections

between Glenville and an abundance of nature...

>more

Take a tour of our proposed Counter Cultural Gardens.

>more

Once Upon a Rustbelt | Party Center | Raw Materials | Subscribe | Urban Underpants