| Vol. 1, Issue 4 | |

|

Words: Steve Rugare For this issue, Hotel Bruce gave us a particularly tough assignment: Find a compelling design response to the problem of affordable housing in Ohio City. Why is it so tough? Partly for reasons particular to Ohio City (and we’ll return to those in a minute), but mostly for reasons having to do with current thinking on the issue among planners, developers and architects, all of whom contribute to—or simply ignore—the economic and social dysfunctions that have made our society inept at providing suitable housing for many of our most vulnerable citizens. There are experts in the field who know a lot more than us about those dysfunctions and could explain why private and public institutions have such a hard time delivering an adequate supply of housing suitable to the needs and means of so many people. But we were faced with a deadline to get something interesting on paper, so we were more concerned to look at what’s happening in architecture and urban design. Upon reflection, we didn’t find that situation too encouraging either. For the last few decades, most architects have been pretty much content to churn out the high-end products that private developers seem to want. (In Cleveland right now, this usually means $300,000 townhouses with inconvenient floor plans but very fancy bathrooms and kitchens). This ought to be an embarrassment to the profession. During most of the last century, architects were very concerned with the problem of housing for people of modest means. This was particularly true during the heyday of modernist architecture, and Cleveland was actually a pioneer in the modernists’ program of decent housing for the poor.

Just north of the Shoreway from Ohio City is the Lakeview Terrace public housing project. If you take a ride through the place, you probably won’t believe that this was a nationally celebrated achievement when it opened in 1937. Places like this promised clean housing, up-to-date facilities, and the modernist ideal of a sunny, green setting. Actually, there were waiting lists of working poor people who wanted to move into these low cost apartments. People had to prove that they were employed and of upstanding character in order to qualify. Obviously, our perceptions of places like Lakeview Terrace have changed completely since the 1930s and 40s, largely because their condition has changed so dramatically for the worse. Fair enough, but architects tend to blame the problems solely on design, ignoring the social forces that messed up American public housing. Many of them have thrown out the idealism that informs modernist housing projects along with the planning principles. It began with the early postmodernists of the 1970s, who were motivated by a zeal for revenge against their modernist forefathers. As they told it, the modern movement “died” when the disastrous Pruitt-Igoe project in St. Louis was dynamited in 1971. Their story focused mostly on the style of the buildings, giving less attention to the fact that Pruitt-Igoe (built in 1949) marked a break in scale and attention to community from earlier public housing. It was higher density, had fewer amenities and was almost ideally suited to become a warehouse for the poorest of the poor. Since the 1980s and 90s, architecture journals have been dominated by the glitzy object buildings of the leading postmodernists and deconstructionists. To say the least, there has been something of a disconnect between housing activists (interested in low-cost construction and modest alternatives like co-housing developments) and the design community— and between the very few designers who really care about these issues and the rest of the profession. You won’t find low-cost housing as a studio project in many architecture schools, and you won’t find much about it in most of the magazines. That’s not to say that there hasn’t been activity. There have been a number of efforts to define new concepts for affordable housing , and almost all of them could be relevant to the complex situation in Ohio City. A number of architects have produced innovative projects for affordable, cooperative or even single-room occupancy (SRO) housing, often with various sorts of social services included in the facility. The recent foreclosure of the Jay Hotel in Ohio City points to the need for something of this sort.

Even as the neighborhood prospers, it continues to be frequented by a substantial population of homeless or marginally housed people, many of them with multiple and overlapping substance abuse and mental health problems. Their situation might be addressed compassionately by providing updated and more socially responsible versions of the traditional “flophouse” (e.g. the Jay). One of our colleagues at the Urban Design Center,

Gauri Torgalkar, designed one of these supportive housing projects

for a site on Lorain Avenue, southwest of the core of Ohio City.

She worked with activists from St. Patrick’s Church in developing

the program for a facility that would include housing, a garden,

community rooms, and facilities for drug and alcohol treatment.

While this model may be a bit too paternalistic for many, it could

be just the thing for some people who really need help putting their

lives together. (Click here

to take a look at a PDF file of Gauri’s project.) Of course, the reason the program has “worked” is that many of the sites (like Riverview) have actually become quite valuable, and the result sometimes is little more than federally subsidized gentrification. Experience elsewhere suggests that very few of the residents who’ve been displaced at Riverview will end up living in the New Urbanist enclave that will replace it. (One of our students at the Urban Design Collaborative, Courtney Wise Lepene, is doing a thesis project to try to improve on the record of the Hope VI program in a design for Lakeview Terrace. Check back here in May to see how that turns out.) As you can see, there’s a lot to think about. Looking at Ohio City, which probably has more positive physical features than any neighborhood in Cleveland, it should be pretty easy to take “cues” from the context and come up with designs that help reinforce the good things that are happening. But add issues of affordability and social justice into the design mix, and it’s hard to decide which cues to take. As we started batting around ideas, every observation that seemed useful to generate design ideas also came with an “on the other hand.” That’s fine in theory, but designers eventually have to start making marks on paper. Here, in highly condensed form, are the minutes of our deliberations:

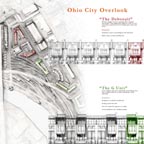

Obviously, we did a great job of running circles around ourselves. We finally decided to extricate ourselves from our troubles by, in a sense, dramatizing them. We took a highly visible and fairly impossible site—the bluff just to the east of the West Side Market—and tried to find an expressive or poetic approach that invites the inexorable forces of gentrification to cuddle with the framework of a micro-economy that might give a leg up to some of the poorest of the poor. In addition to its location right near the heart of the neighborhood, this site has two other intriguing features: 1) There’s some basic unfinished urban business to the east of the Market. The enormous parking lot and the Riverview public housing have left a tiny, isolated fragment of what was once the Hungarian neighborhood around St. Emmeric Church. This no-man’s land needs some help, especially as the city tries to address the river valley more positively. 2) The planned Hope VI project for the Riverview site, which has the virtues and limitations described above, provides an instructive contrast/backdrop to our efforts. The plan we developed has a number of significant features. Some of them are just good urban design, but some go in more provocative directions... Replacing the surface parking lot A new parking structure north of (or behind) the Market replaces the current lot. It’s wrapped with a mixed-use layer, mostly of small apartments. The main portion of the structure is flat, so the top level could be used for outdoor recreation.

St. Emmeric and its environs A new green space east of the market organizes traffic heading to the garage and creates a setting for a mixture of townhouses and more affordable “carriage house” units focused around the church. All of the other "obsolete" existing buildings are removed.

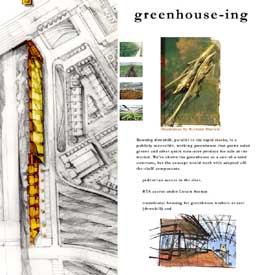

Greenhouse passage Running downhill (toward the river) and parallel to the Rapid tracks, is a publicly accessible, working greenhouse that grows salad greens and other quick turn-over produce for sale at the market. We’ve shown the greenhouse as a one-of-a-kind structure, but the concept would work with adapted off-the-shelf components. Since the greenhouse also doubles as a novel passage into the valley, we’ve cut quite deeply into the slope, leaving the church perched above a substantial retaining wall and making it a highly visible beacon from more than 180 degrees around it. As the greenhouse passes the church it sprouts a series of small housing units. This wouldn’t be a desirable site for market rate housing. The rail line and the truck route through the valley are problems. In addition, the site isn’t all that accessible, which is one reason a lot of homeless people already camp out in out-of-the-way spots along the bluff. But its visibility and proximity to the West Side Market make it an ideal site for a specialized transitional housing project. Interested homeless people could live and work in the greenhouse. Meanwhile, they still have good access to transit and the social services that churches and public agencies have developed in the neighborhood. This “micro-economy” would be a compelling model of sustainability, and it could be extended further into the agricultural terraces (see below).

Agricultural terraces Below the church we’ve cut a series of terraces that function as the outdoor part of our mini-farm. On some of the terraces, we’ve placed more housing in the form of pre-fabricated units converted from shipping containers. Think of these as a somewhat formalized and more productive version of the “shanty-town” that already exists in the underbrush of the bluffs. Taking advantage of the terraces, the shipping containers can be placed in two-story pairs, the lower opening to the terrace below and the upper to the next one up. The gentle arc of the terraces, the beacon of the church and the line of the greenhouse (illuminated at night), would form an arresting image for commuters on the rapid both by day and night.

Riverview Terrace The concept also includes some re-working of the Hope VI project for Riverview. The site plan is simplified and rows of subsidiary “carriage house” units are introduced, along with a multi-story block at the “gateway” coming from the market. The idea here is to introduce as wide a variety of housing options as possible within an integrated fabric. Ideally none of these would have to be subsidized. Rent on the affordable carriage houses might help make the townhouses more affordable for middle-class people.

Riverside Path Finally, we’ve introduced a bicycle and pedestrian path extending along the edge of the bluff from the Detroit-Superior bridge, below Riverview, and swinging around St. Emmeric and up into Market Square. Not only would it make a nice connection with the lakefront bike path system, but it would bring people through the transitional housing/farm development. The point is not just to house the people who need it, but make the resulting setting as inviting as possible for everyone.

Conclusion Is this going to happen? Probably not. We’ve ignored tons of practical impediments, starting with the stability of the slopes on this site. But we think this design does make some points worth thinking about as we contemplate the future of America’s poorest city. Chances are mid-size cities like Cleveland will have to go it alone in the next few years, maybe longer. The kind of micro-economy based, cooperative housing we’ve proposed here might be one way to keep a lot more people from becoming homeless and hopeless. And it might actually work a lot better on less constrained sites with less challenging terrain, of which Cleveland has plenty. It’s not going to produce the big return on investment of luxury townhouses or urban McMansions, or do much for the tax base. So Cleveland certainly will need its share of those, too. But with families changing radically, with economic “restructuring” leaving more and more people behind, and with the federal and state governments offering no help for the foreseeable future, this proposition might offer some hope and might even be able to pay for itself. It’s not the solution, but it’s an intriguing step.

Additional art:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

We took a highly visible and fairly impossible site—the bluff just to the east of the West Side Market—and tried to find an expressive or poetic approach that invites the inexorable forces of gentrification to cuddle with the framework of a micro-economy that might give a leg up to some of the poorest of the poor.

| What's

Feature Well? What would the city look like if the new guard were in charge? Each issue focuses on an area in the city that could benefit from some creative energy with feature articles that offer a vision for a new Cleveland, Q&As with the movers-and-shakers who are making a difference, and visual evidence of how the landscape might look if creatives were calling the shots. |

![]() Also in this issue's Feature Well...

Also in this issue's Feature Well...

In the battle between affordable housing and luxury living, it's clear who's winning in Ohio City

Once Upon a Rustbelt | Party Center | Raw Materials | Subscribe | Urban Underpants