| Vol. 1, Issue 4 | |

|

By Lindsey Bistline

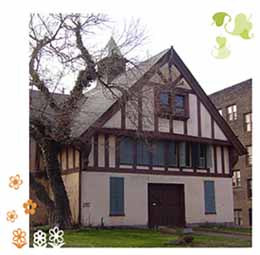

Artist Carlo Maggiora may be one of the few remaining true gentlemen around. At a time when having a palm pilot and the latest camera cell phone seems like a necessity, he lives and works in a barely renovated, unheated carriage house, tucked away between Euclid and Chester on East 73rd Street. It is one of only two carriage houses left in Cleveland (the other is on land owned by the Cleveland Clinic), according to Maggiora, and was once part of a set of buildings that included a mansion. The mansion was torn down years ago, the land parceled off, and all that is left is the Tudor-style carriage house, built in 1898.

One could drive past the place a hundred times and never notice it. It’s easy to miss, masked by abandoned lots and boxy commercial buildings along that section of Euclid. But once discovered, you wonder how you ever missed such a beautiful piece of Cleveland history, sitting in the middle of what used to be Millionaire’s Row, surrounded by majestic old trees and a stunning view of the city skyline. But even considering the fabulous view (left), and given Maggiora’s interest in history, why buy a broken down old carriage house?

Rediscovering the city Carlo Maggiora grew up in Italy, but his mother was from Cleveland, so he spent his summers visiting his grandparents in Cleveland Heights. When he was 17, his family returned to the States and settled in South Euclid. At the age of 26, he contracted a common Cleveland malady—an itch to start a new life someplace else. “When I was in my twenties, this was the absolute last place I wanted to be,” he admitted. After ten years of globe trotting that included living in both New York and Los Angeles where he worked as a movie cameraman, he felt an inexorable pull to return to Cleveland that even he can’t fully explain. He gave in to that pull, and when he arrived, he “didn’t have a dime.” A friend owned a warehouse in Midtown on E. 71st and offered to put him up for a while. He accepted, and spent the next three years getting reacquainted with the city sans a car. Each time he walked by it, the old building on the corner of E. 73rd and Euclid fascinated him. The lawn was always trimmed, but the windows were boarded up. “It looked like a ghost house from the outside. It was always sort of mesmerizing… But it never occurred to me that I might be living here someday.” The owner at that time was a bit of a local celebrity who taught art at Tri-C and reportedly threw huge swinging parties. It was rumored the cantankerous old man had a fantastic art collection hidden within the building’s moldering walls. When he died in the house, his family liquidated his belongings, and the building was left to a man who had worked for him. For a few years, the carriage house sat empty except for local, small animals and rodents who happily moved in. The beautiful trees went un-pruned and the lawn grew wild. Vandals visited and broke every window that wasn’t already broken or boarded up. But Maggiora kept walking by the property, still captured by its old-world charm and historic beauty. When he heard through friends that the property was for sale, he immediately contacted the owner. At first, the owner was lukewarm to Maggiora’s offer, but eventually came around. Maggiora secured a loan, but when the bank sent an inspector out to assess the property, they backed out of the deal in a hurry. Even though the previous owner had the parcel of land declared an historical property, the bank claimed it was classified as a commercial property and wouldn’t fund a loan to buy it. Cleveland Restoration Society to the rescue Discouraged but determined not to give up, Maggiora contacted the Cleveland Restoration Society (CRS) at the suggestion of a friend. CRS seeks to protect architectural treasures in older neighborhoods, and to counter the population pattern of moving further from urban centers. Homeowners can use CRS financing or consulting services for a variety of home maintenance and improvement projects. The organization agreed to inspect the carriage house, and “expressed an immediate interest” in its preservation. CRS put Maggiora in contact with Key Bank through their Neighborhood Historic Preservation Program. With the help of CRS, Key Bank, and Bill Gaydos—an appraiser of old buildings and properties who provided a second opinion —Maggiora finally purchased the carriage house in February 2003 for approximately $148,000. Now what? After the first flush of pleasure at finally holding the keys in his hand, Maggiora felt a bit apprehensive. Every window in the place was broken, there was little to no lighting, it was absolutely filthy, and he had birds and squirrels for roommates.

“It was one of those 10 degree Cleveland days, and [I] basically wondered, what did [I] just do?” he said, seeming a little chagrined at the memory. But part of the fascination of buying a place like this is the prospect of fixing it up. The first thing he tackled was the roof. Oh, the roof. It cracked. It peeled. It leaked. It did everything a roof isn’t supposed to do. Originally, it was made of a beautiful, durable slate tile; however, the previous string of owners committed the near criminal act of putting first tarpaper, then a modern asphalt shingle roof over the tiles. During installation, workers punched nails through the slates beneath, utterly destroying the original slate tiles. Maggiora knew “the biggest job from day one was getting the roof done.” Using most of the money from the $42,000 CRS rehab loan, he hired a roofing company to remove the old roof and replace it. The job required so many men and so much equipment that “it was like a military operation,” Maggiora recalled.

Once the roof was finished, the focus turned inward. Carlo decided to go on a cleaning and purging rampage. Far from being the light-filled studio he had in mind, the interior was a labyrinth of tiny, dark rooms filled with junk. Many of the walls of the teeny rooms were made of haphazard materials like corrugated fiberglass, and roofing materials. The third floor was covered in dark wood paneling,

circa my aunt’s rec room in the early 70’s. Instead

of a priceless art collection, he discovered old appliances from

the 40’s tucked behind the walls. Finally, when he had the

place down to its bare bones, the beauty and craftsmanship of its

original red painted wood floors and exposed beams could be appreciated. The moment you speak to Maggiora, you get the feeling you’ve just taken a step back. Back from life, back from our fast-paced world, back in time. “I should have been a country gentleman,” he jokes, referring to the wealth that would accompany such status. But the truth is that the house perfectly suits the man inside. I follow him across the open expanse of the kitchen on the second floor, wooden floorboards creaking with our weight. A narrow staircase hugs the wall, and a sign with Chinese symbols marks the bathroom. He leads me through a barrier of industrial clear plastic refrigerator curtains, and it’s amazing how well they contain the heat emanating from a little, wood-burning stove in the corner of his office/bedroom. The curtains separate his office from the kitchen, which is clean, functional and utilitarian with its restaurant-style stainless steel sink and mobile sprayer. A bowl of green apples provide some relief from the white walls and exposed floorboards.

True to his nature, he offers me the seat closest to the stove, which he purchased a few weeks before. As I try to imagine getting through a winter in Cleveland without heat, light peaks through the cracks of the floorboards from his workshop below.

Modern machinery and tools have replaced the horses that used to be stabled here. Now Maggiora uses the space to design and build furniture, as well as mounts for museums and private collectors. His Spartan living style is reflected in his work, which is clean, modern, and refreshingly simple—a true tribute to the mantra of form follows function. “Lighting is one of the most important things in any task,” he says, explaining the large opening he created at the back of the desk sitting in his office. The modern simplicity of its lines is austerely elegant. He notes that a recurring theme in furniture is truth. “Just let things be what they are,” he says. He asks me to picture the drain in the middle of a floor; “if you could hose everything down, that’s what my work is like,” he explains. Just the bare necessities. When Maggiora first moved back to Cleveland, he started his own company, making mounts for art museums that weren’t equipped to handle large pieces. In particular, Cleveland Museum of Art needed his help to mount many of the heavy stone pieces in the restored Egyptian gallery.

As we talk, he pauses to put more wood on the fire. Living and working in such a space creates a chore environment, he notes. Instead of turning up his thermostat when it gets cold, he plans how much firewood he’ll use throughout the winter, without going over so he doesn’t have to store it all summer. Still, even as he talks of the difficulties of finding discarded pallets to burn, you get the feeling he wouldn’t trade it for anything. He calls the winterscape of Midtown and Euclid Avenue paradise. “There’s something really glorious [about] Euclid Avenue” in the winter. When he looks out his window to the empty lot across the street in the dead of winter, he is struck by the silent beauty of Midtown. It possesses its own brand of old-world charm, and is so “dead quiet” that it could be a scene from the early 1900’s. The quiet and absence of people is “kind of lunar despite its familiar sites. You certainly don’t get that in other big cities,” he says. On winter nights when it’s “cold and snow covered, and it’s a straight shot to downtown…” he trails off for a moment, lost in thought, then, “It’s a desert with thousands of buildings,” he finishes. During the summer, Maggiora walks to nearby Dunham Tavern Museum when he needs some quiet time or inspiration. Established in 1824 and opened to the public in 1941, Dunham Tavern is a non-profit museum and the oldest building still standing on its original site in Cleveland. Once part of the Buffalo-Cleveland-Detroit post road, over the years it has served as a meeting place for the Whig party, a tavern, and studio space for artists.

The Tavern’s urban garden is what draws Maggiora. “Once you’re in there, it’s another world,” he says. The garden is practically deserted during the week, and is “like a private garden [with] spectacular flowers and plantings.” Maggiora doesn’t know if any of his neighbors are artists, in fact, all he sees on a regular basis is a mailman, an apartment building next door, and quite a few commercial buildings. That doesn’t faze him, though. “The problem with the suburbs is they’re so perfectly manicured,” he says. Besides the colorful history of his home and easy access to historical sites like Dunham Tavern, he cites what the calls “the utility factor” as a huge plus of living in the carriage house. He has an enormous workshop on the ground floor with street access through a rolling garage-style door, and the building is extremely sound. He points to foot-and-a-half thick I-beams as proof. For his groceries, Maggiora usually shops at the Cleveland Food Co-Op in nearby University Circle. When I steer the conversation back to his work, Maggiora stumbles a bit. Though quite articulate, he hesitates to put adjectives to what is presumably closest to his heart. “I just make things that I think…” he trails off, glancing around the room for inspiration.

He points again to his desk, pulling out a large drawer that spans the front of the piece and rolls out smoothly at the touch of his fingers. Inside is a large “crumb tray” into which one can scoop all the stuff on the desktop at the end of the day, providing a clean surface to start off the next day. The top portion of the desk is punctuated with pigeonholes. Again showing his love of history, he notes that in the past, “every hotel in the world had pigeonholes behind the desk,” which provided the inspiration for these. He is also humble when it comes to his work, explaining that all of his ideas are taken from other applications. It is only when we discuss current trends in furniture that his gentlemanly demeanor darkens. “Industrial processes...carved to look like hand made objects really irk me,” he says. Much of today’s popular furniture is mass produced, and stores are rife with cheaply made pieces that appear handmade, unique and/or antique—cherry stains instead of cherry wood, oak armoires with particleboard backing—when in reality they’ve just tumbled off an assembly line. And that’s just it. Carlo Maggiora is as far from an assembly line as anyone could be. He is an urban pioneer, sitting in his 19th century carriage house, reading Italian newspapers online and creating exquisite furniture. Hopefully, other artists and residents interested in preserving Midtown’s history will follow. Until then, he’ll be waiting. Waiting for the rest of the city to discover Midtown the way he has. |

|

What's Inny and Outty? Are you curious about the homes and lives of Cleveland’s most creative people? Inny and Outty takes you inside some awe inspiring renovated dwellings and then expands the view to explore how creatives transform their landscapes, streets, commerce and more. Plus, you’ll get tips on how to incorporate these experiences into your own lives. |

Once Upon a Rustbelt | Party Center | Raw Materials | Subscribe | Urban Underpants