| Vol. 1, Issue 4 | |

|

A visionary shift from industrial powerhouse to biotech hothouse By Steve Rugare and Steve Manka

If it's possible to sum up Cleveland’s problems in a sentence, this seems like an appropriate one—the city hasn’t found a way to shrink with its declining population. We now have less than half a million people knocking around in a physical container built for twice that number or more. The result is too much land but too few sites with any opportunity for a return on investment. Rather than spreading the available capital around evenly, we need to concentrate it into relatively few places to create viable islands of development. Much of the rest of the city needs to be “banked” into low-density uses that enhance the value of the viable nodes. We decided to take on the challenge of imagining an appropriate urban future for the area around the former Hotel Bruce, because the site exemplifies the key challenges posed both by Cleveland’s current situation and by the limitations of urban design theories and development strategies. “New Urbanism” is all the rage these days, and it tells us a lot about what the islands of development should be—pedestrian friendly, close-knit, with a rich mix of uses. However, it tells us very little about the surrounding, low-density sea, about the in-between spaces of a shrinking city. In addition, planners and designers don’t really have the legal and financial means to rationalize the worn out patches in the urban fabric and implement careful, site-specific plans. The city and state are broke, and the only source of public funding seems to be transportation dollars. This often results in a deranged sort of urbanism that is charged with finding after-the-fact rationales for infrastructure investments, even when the infrastructure occurs at a site where there is no demand for development and where pre-existing environmental qualities offer little potential for place making. While the public sector offers what carrot it can, private money has come to favor a kind of thematic “lifestyle” development based around a blandly up-scale boutique culture. To hear most commercial developers talk, there must be an endless supply of laptop toting, latté chugging, on-the-go, creative, affluent people out there, just waiting to occupy new “urban villages.” You’d think no one else’s money was even green. Population loss and the lack of appropriate development strategies have resulted in a profusion of sites like the midtown Euclid corridor—leftover places that pose novel questions for urban designers. We formulated them like this: Question one: Why adhere to contextual design when the context is so damaged or vacated that it gives weak or mixed signals?

Question two: Much of Cleveland was settled very quickly between the 1880s and the 1950s, and much of it has been de-settled just as rapidly. We think of urban revitalization as a process of infill development, capitalizing on the remaining fabric, but only a relative handful of areas in Cleveland are obvious candidates for intensive re-settlement. These are places like Ohio City and Tremont, where there is the right kind of surviving housing stock and where the scale of the street network is unusually intimate. What procedures can make sense of midtown Euclid, where very little is left to work with and where the street network (especially Chester Avenue to the north) isolates the site from its surroundings? Question three: How does one make a distinctive and rooted urban place when a culture driven by marketing and entertainment favors a generic theme attached to anything new? More generally, how does one make a valid urban place while employing the buzzwords and “consultemes” (e.g. “creative class”, “innovation”, “active lifestyle”) that excite the glands of the people with money? Attempting to address these questions, we formulated three possible development approaches for the street around the former Hotel Bruce. We sketched each out in plan, and aspects of each made it into the preferred solution we finally developed. Option 1: Developer-friendly "new urbanism" with catalytic shards of the real

The idea here is to use the familiar approach—taking cues from the context and attempting to create a facsimile of the historic fabric. We hoped we could avoid the generic environment that can result from this procedure by including a few site-specific gestures (such as a new Hotel Bruce) to recall some of the social complexities of the place’s history. As you might gather from the comments above, we had doubts about this approach because it often looks and functions like the work of carpetbaggers from the suburbs. More importantly, new urbanism uses buildings to do all the work of place making. The likely result in this case would be high vacancy. We propose that only one small section of the study area could support this approach, the group of surviving loft structures near Gust Galluci’s at Euclid and East 65th. Option 2: Drive-by investment park Here we were inspired by the proposal to build biotech start-up space in this area. At the same time we had to keep in mind the record of this sort of “new economy” investment. We’ve already had one highly touted biotech startup do its basic research in Cleveland, only to pack up after a couple of years and build its production facility in California. Bearing in mind that salvation through biotech might be a little bit of a mirage and that many of the businesses in question will come and go very quickly, we wanted to develop a flexible architecture for the start-ups and fly-by-night investments of the new economy—a sort of glass tent city that might de-camp at any moment.

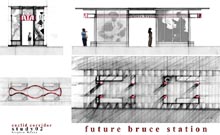

To address the street, these buildings would be the armatures for large-scale (but equally evanescent) public art that could respond to the speed of travel between the two hubs on the Euclid corridor. We think this concept expresses some of the transience of the urban environment and the speed with which settlement and de-settlement have occurred. Also, it creates a distinctive setting for new investment without sapping energy from more competitive areas struggling to achieve density and urbanity. On the other hand, it’s less successful in meeting the difficult challenge of making social and physical connections to the north and south of the corridor, and it undervalues the significant (though few) older buildings in the area.

Option 3: Improvisation district Trying to give some social relevance to new investment, we imagined introducing new uses related to the medical industry while providing a symbolic framework for reviving old entertainment uses. Biotech and entertainment could coexist within a loose fabric based on flexible exploitation of historic and new structures. Ideally this would lead to chance meetings between knowledge producers and cultural producers within a semi-nomadic population (performers, researchers, service industry workers, etc.). We even considered the idea of a magnet school of music and life sciences to further reinforce the theme. Ultimately, we had a hard time figuring out how these goals might be achieved, either visually or socially, and we wondered whether the new district could attract the needed investment. Obviously, the issue here is making a substantive connection with social and cultural memory and with the life of the surrounding neighborhoods. We tried to keep those priorities in mind as we went to work.

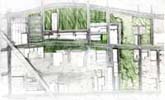

Preferred solution Our more developed plan includes features of all three of the preliminary options. These are bound together by a critical background feature: The cultivation and restoration of the de-settled landscape. Drawing on emerging concepts of “landscape urbanism” we began generating concepts for agricultural re-use of large portions of the site—“returning” it to the character it had about 150 years ago, before it was urbanized. Specific interventions include:

Against this background of re-cultivation, we propose a number of new or re-used structures. These draw on the development concepts described above, and their functions and meanings can be organized around three themes: New uses and old fragments Our flexible biotech incubator space follows a different physical model from the mute suburban office park currently proposed. A light, glazed frame creates an unbroken linear band between the orchard and the gardens along Chester Avenue. Several stories of well-serviced space can be let to small and large tenants for research and start-up production. Graphics on the glass walls recall various phases of the corridor’s past, both prestigious and popular, and overlay glimpses of the activities that could lead to a future re-birth.

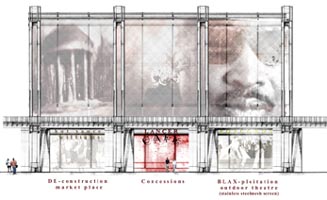

Relatively good automobile access makes the East 55th Street intersection a potential site for big box retail. Rather than a generic chain store we propose a “Deconstruction Depot” where fragments of old structures demolished as part of the re-tooling of Cleveland’s housing stock could be re-sold to people restoring buildings or building anew in Cleveland and its suburbs. The buildings on the south side of Euclid could house more specialized salvage brokers. The parking lot doubles as a drive-in movie theater, with the screen structure housing convenience vending for shoppers and biotech workers. Memory in Transition

The images screened on the Biotech Incubator and both sides of the drive-in theater screen are fragmentary and evanescent, reflecting the rapid pace of settlement and de-settlement in a site that was essentially countryside less than 150 years ago. They include reminiscences of musicians and entertainers, fragments of the houses and buildings that once lined the street, of the vehicles that once traversed it, and of the marginal characters that made it their own after its heyday. Many of these memories condense at the West end of the Biotech Incubator in a new Hotel Bruce, which will feature leisure opportunities and a bit of nightlife for the researchers and their visitors, as well as neighborhood residents. A further layer of memory is found in the re-cultivated area around the Dunham Tavern Museum, where the reconstituted stream begins to bring back elements of the site’s pre-urban character. Gourmet Ghetto: A settlement for urban pioneers

Lessons If there’s one thing we’ve learned working in Cleveland over the last few years, it’s that getting designs implemented in this town is really tough. Even relatively modest proposals can languish when demand is as low— and money as tight—as it is here. We’ve tried to respond to that reality by thinking outside the conventions of current urban design, which too often result in grand master plans that might be realized in some unknown (but always rosy) future. Working a bit more modestly, we’ve tried to devise a series of urban episodes that seem pretty feasible in the near-term. This approach leaves the door open to further development later on, should prevailing conditions improve. In the meantime, it suggests that a shrinking city like Cleveland could be a lot more interesting to live in. Instead of nearly uniform decay, there could be a range of compact but distinctive places to live, work and shop. Instead of tracts of derelict land, there could be an abundance of re-constituted and cultivated landscapes, enhancing quality of life and creating a degree of sustainability that no one even imagined during the boom years of the last century.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What's Feature Well? What would the city look like if the new guard were in charge? Each issue focuses on an area in the city that could benefit from some creative energy with feature articles that offer a vision for a new Cleveland, Q&As with the movers-and-shakers who are making a difference, and visual evidence of how the landscape might look if creatives were calling the shots. |

Once Upon a Rustbelt | Party Center | Raw Materials | Subscribe | Urban Underpants